Pinpointing a specific motive for painting is often challenging, so I create art without a particular form. Sometimes, I start with a clear motive, but it usually fades as I progress. Other times, I begin without a specific motive, only to have one emerge as I perceive a set of marks or feel a predisposition that suggests a direction for the artwork. Embracing the formless while being open to accepting form is a complex but essential characteristic of painting.

PAINTING

Painting is all about the way I apply paint to the support. Choosing the right tools and surfaces is crucial. Most importantly, it's about the process. From the moment I decide to start painting until I finish, that period is painting itself. The amount of confusion and clarity I go through is a vital aspect. When I begin to paint, I usually have vague thoughts about colour and composition, but these rarely remain the same until the end. As I paint, my thoughts change, and I often decide to go in a direction I did not anticipate. I frequently feel restless and even anxious about the outcome of my gestures and decisions. I am often surprised when something extraordinary emerges on the canvas. Sometimes, things that I initially think won't work—or are mistakes—transform into something good. I usually don't know when I will finish a painting; I only know when, during the process, I reach a point that gives me the confidence to decide that I have finished painting. All of this is closely related to the result. I have to like it. Yes, I have to. However, the fact that I like the painting does not mean it has to be conventionally beautiful.

WAYS OF BEING OUTSIDE LANGUAGE | FORMAS DE SER/ESTAR FUERA DEL LENGUAJE

FERNAND DELIGNY

Autism and its "WAY OF BEING OUTSIDE OF LANGUAGE"

To act for nothing, the endless movement, that is at the limit of what we normatively understand by productivity.

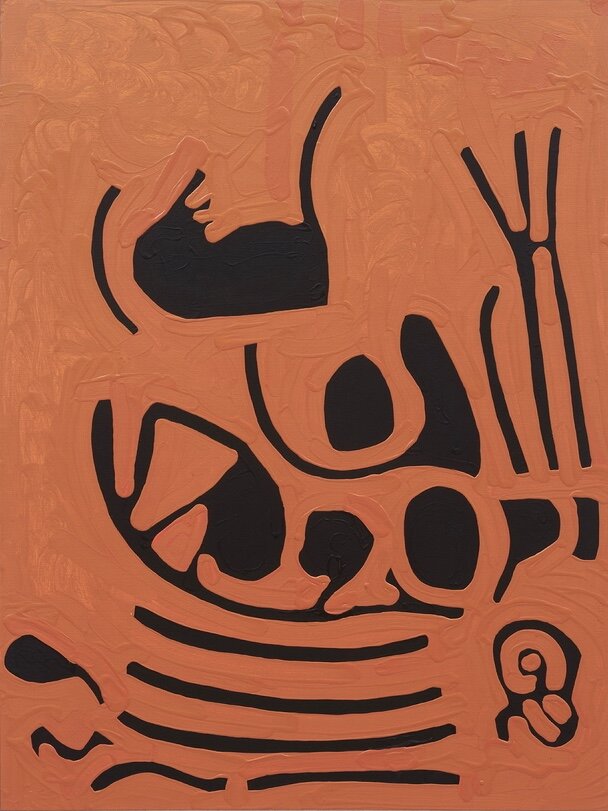

MARLON MULLEN

Marlon Mullen, artista autista y con afasia expresiva (dificultad para producir lenguaje hablado, manual o escrito).

Formas cerradas, superpuestas, entrelazadas / Bloques de color-forma / Colores sin variaciones en valor / Pinceladas texturas

El acto de pintar como performance que no proviene ni regresa a la lectura (lenguaje). (Sasha Frere-Jones, Artforum, Abril 2019, Vol. 5, nº8)

Marlon Muller, Untitled (P3201), 2014, acrílico sobre lienzo, 61 x 61 cm, Jack Fisher Gallery.

PAINTING AND CRITICAL THINKING

“The new pedagogy has been endorsed mostly by younger painting professors but a few geezers too, who see painting as best learned through critical thinking, a method borrowed from literature and the social sciences.

The approach benefits disciplines based in words, and I use it myself when teaching modern art history and humanities seminars. But it’s a disaster when used to teach painting, […]

Applied to painting, critical thinking too often ends up calling into question the very medium—a deconstructionist impulse that particularly sabotages beginning students. Playing baseball or tennis requires accepting the game as a whole, and so does painting. But unlike baseball or tennis, painting is an open-ended pursuit without any numerical victory or defeat. It’s fraught with subjectivity and uncertainty. It is, as an artist I know has said, one semi-mistaken brushstroke after another applied until a kind of truce against the possibility of a perfect painting is reached.

With today’s identity-conscious students wanting, right off the bat, to express in paint ideas about anything from gender crossing to wealth inequality to global political oppression, competence in painting’s traditional skills has become almost a no-go zone. Painting professors have retreated to merely “supporting” and “nurturing” student painters, asking only that students “articulate” what they’re trying to do — that is, to retroactively apply critical thinking to their works. As a result, a lot of students leave painting courses prematurely feeling good about themselves because they’re able to talk some pretty good contemporary smack about art. But few have learned much about painting.”

(Laurie Fendrich. Excerpts from How critical thinking sabotages painting, 2016, twocoatsofpaint)

JUAN USLÉ Y EL PELIGRO DEL EXCESO DE REFLEXIÓN SEMÁNTICA

“No creo que las obras anteriores carecieran de ligazones a lo vital. Pero quizá en algunas ocasiones la especialización del lenguaje, sobre todo cuando va precedida de un exceso de reflexión semántica, conlleva una pérdida de riesgo, que desemboca en una carencia de pasión a la hora de ejecutar la obra.

Pasión y riesgo que he intentado recuperar, persiguiendo un mayor diálogo, un mayor intercambio, sobretodo en lo gestual y en la propia acción de pintar. […]

El discurso y la vivencia coinciden en el momento de pintar.”

(Juan Uslé, “Pasos y palabras”, p. 14)

Shape: The Boundaries of Masses.

Outside/inside, open and closed shapes: Alona Harpaz, Paco Shánchez, Marlon Mullen, Charline von Heyl.

The Outline. The Background as Figure. Flowers, Furniture, People, Shapes

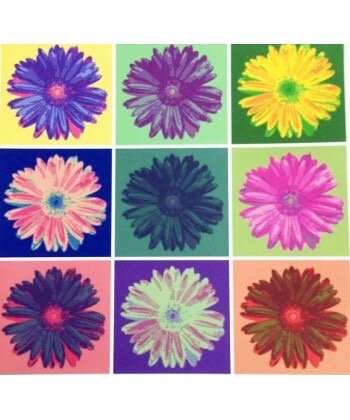

What is decorative and what is not decorative? Who says what is decorative and what is not decorative? Has any sense to speak about the decorative? Warhol, Matisse, Haring, …

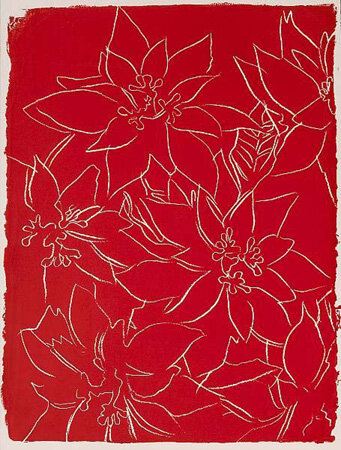

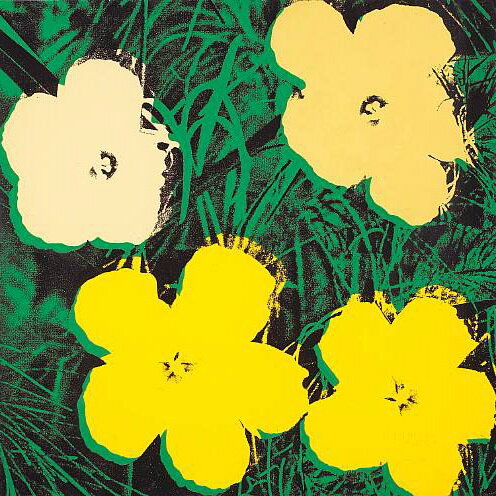

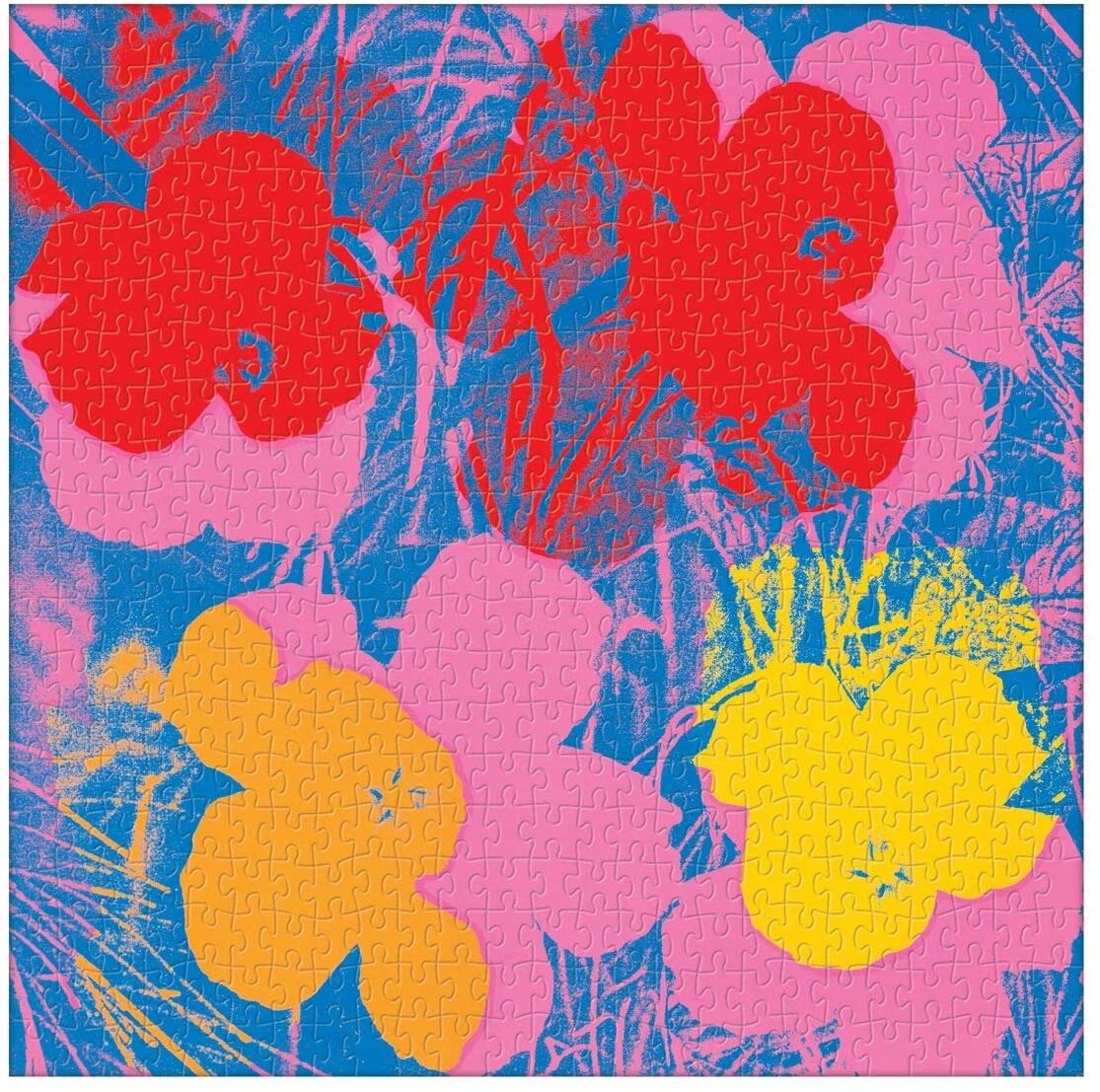

Warhol, Flowers

Warhol started to paint flowers in 1964, after his violent piece Thirteen Most Wanted Men. His flowers were based off a photograph of Hibiscus flowers taken by the then executive editor of Modern Photography magazine, Patricia Caulfield. Warhol did not paint these flowers from nature but admitted he appropriated one of Caulfield’s photographs. In 1966, Patricia Caulfield sued Andy Warhol.

Ronnie Cutrone (Warhol’s main assistant): “You have this shadowy dark grass, which is not pretty, and then you have these big, wonderful, brightly colored flowers. It was always that juxtaposition that appears in his art again and again that I particularly love”.

Warhol decided to paint them on a square format: “I like painting on a square because you don’t have to decide whether it should be longer-longer or shorter-shorter or longer-shorter”.